After reading Marshall Berman’s All That Is Solid Melts Into Air.

The natural world is not much present in his analysis, or that of most of the social critics I have ever read. But it is increasingly clear to me that attempts to make overarching sense of human life collectively or individually without looking at the biosphere as a whole are at the root of our intellectual paralysis – they are literally dead-ends.

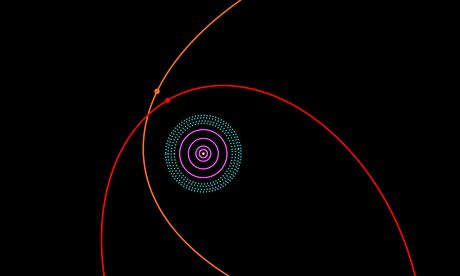

Whenever we stop drugging or deluding ourselves with what some have called the “secular religion” of progress, we become aware that we live now on a knife-edge, the very tip of a whirling blade that unceasingly slashes and shreds and uproots everything in its path, leaving the ruined mess of the past in its wake. Some elements of that past weren’t worth mourning, some may have deserved to die – but others were veins coursing with lifeblood that lie gashed and emptied now. It makes no difference to the knife of modernity; it doesn’t cut judicially, with skill and care as a sculptor cuts and shapes clay, with arduously obtained ability and a profound understanding of natural forms. It cuts and slashes because it is the raison d’etre of the knife to cut and slash.

We look for a home in this world but home is out of reach; we look for home within ourselves but within ourselves there is nothing without the world.

All around us and intimately harbored in the minutest units of blood and tissue of our bodies is the web of life, the enormously elaborate, interlaced, flowing and breathing world that already made sense without us, that, in order to pulse and circulate and grow and deepen in ever-more fabulous complexity, didn’t need us at all. It didn’t need us to come along and name its parts and try to order them, as we may have tried to pretend to ourselves it did. And perhaps the realization of this utter indifference was a cruel shock to the self-awareness we alone seemed to possess. In humiliating fear, and then in outright loathing, we fought to be free of the web, of the animals that preyed on us, big and tiny, of the storms and shaking ground, of the grueling heat and cold. We tried with every great achievement: combustion, agriculture, architecture, mechanical reproduction – to radically simplify the web of life so that we could have final power over it and eviscerate that horrific apathy.

Out of this long march of fear came the knife. And then, in the 20th century, the Faustian battles to wield the knife, as the sculptor does, but upon the whole world. And now – and now, far from the centers of power and wealth in waking dreams the terrible thought has begun to dawn that we are not in control of it. That even those individuals and groups to whom we have ceded almost unimaginable power are not in control of it. The powerful go blithely on, worshipping the knife, singing its praises; the rest are left to scramble among the ruins they create, of fields and forests, long inhabited niches, egalitarian bonds, desires for belonging and home. We justify, accommodate, or resist, or all of the above at different times, in an unending pursuit of survival. But no one can grasp the spinning blade now.

The web of life, which has dealt with cataclysm and rebuilt itself each time with protean creativity may indifferently still be doing what it always has, retreating now before the knife, its elaborately redundant layers of stability decreasing, its turbulent chaos increasing, its more contingent life forms unregretfully disposed of as it responds to physical necessity alone. So whatever sadness there is at the daily diminution of vividness may only be ours. But “all things desire to persist in their being,” according to Spinoza. And the more you look at other species, the birds and the mammals, even the stoic plants and fish, the more you feel that all species can experience loneliness and melancholy at the ending of their desire.